StreetMaps

Hello!

I have been spending some time recently compiling datasets and reading up on research on my home country of Albania, attempting to understand it from a data-driven lens. In addition to my own anecdotal experiences, I wanted some systematic method of analysing the country’s social, political and lived contexts. One aspect of Albania that recently piqued my curiosity were street names and their patterns. Looking online, I could find no pre-existing dataset that looked at how the roads and streets of the country are named, so I set out to create and analyze one.

For this story, I am going to be using Open Street Map data to analyse gender distributions in street names in Albania’s capital Tirana, as well as other historical or geospatial patterns. To do this, I’ll also use pandas, seaborn and a mapping library called contextily for prettier maps. This first part will focus on gender and street names, but I will be working on a part two looking at years of activity as well as areas of contribution over the next few weeks.

So, let’s get started!

Data Labeling and Visualizations

Here is a peek at how the data from Open Street Map was provided, with a specified set of coordinates to cover the entire area of Tirana:

The data contains 26950 rows, most with a geometry and other associated road type attributes. Interestingly, the same street showed up multiple times in the data, presumably with different sections of a street being mapped at one time. Since the data did not contain a variable classifying names according to their gender, and there is no straightforward way of matching names in Albanian to a particular gender using code, I used my own knowledge of the language to hand-label about half of the dataframe’s rows. The column contained one of the following labels:

- W = women names

- M = men names

- O = other types of names (such as historical events, abstract concepts or last names of famous families)

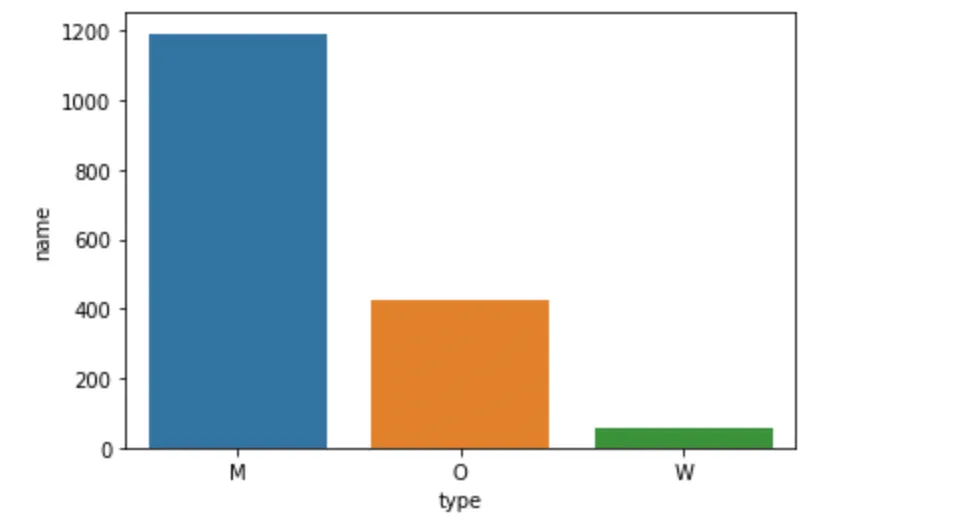

Here is a look at the counts for each gender:

As you can see, women street names make up about 3.3% of the total street names in Tirana, with men names comprising about 71% of the names. This situation is not unique to Albania: 2% of Paris’ streets are named after women and in Rome the number is 3.5%. In these major cities, part of the reason is that city councils which make these decisions historically tended to be overwhelmingly male and white. Indeed, only an average of 36% of local government members across the world are women, with many countries falling significantly short of even this value: for instance only about 25 countries have a 40% women representation in local governments. That being said, the most recent Tirana city council legislature has a 50–50 men to women percentage, which is a step in the right direction.

Street Types and Lengths

OpenStreetMap data also includes tags describing the type of each street row in the data frame, and here is a visualization of how the types compare for genders:

Image by Author

It is interesting to note that there are so many “residential” streets. According to OpenStreetMap the residential tag is “used on roads that provide access to, or within, residential areas but which are not normally used as through routes”. “Living” streets are also very common, defined as roads that “have lower speed limits, and special traffic and parking rules compared to streets tagged using residential”. These are the two types of streets that dominate in Tirana even though they are not main streets, but rather narrower and with less traffic. So, it could be interesting to look into the processes of how they get named.

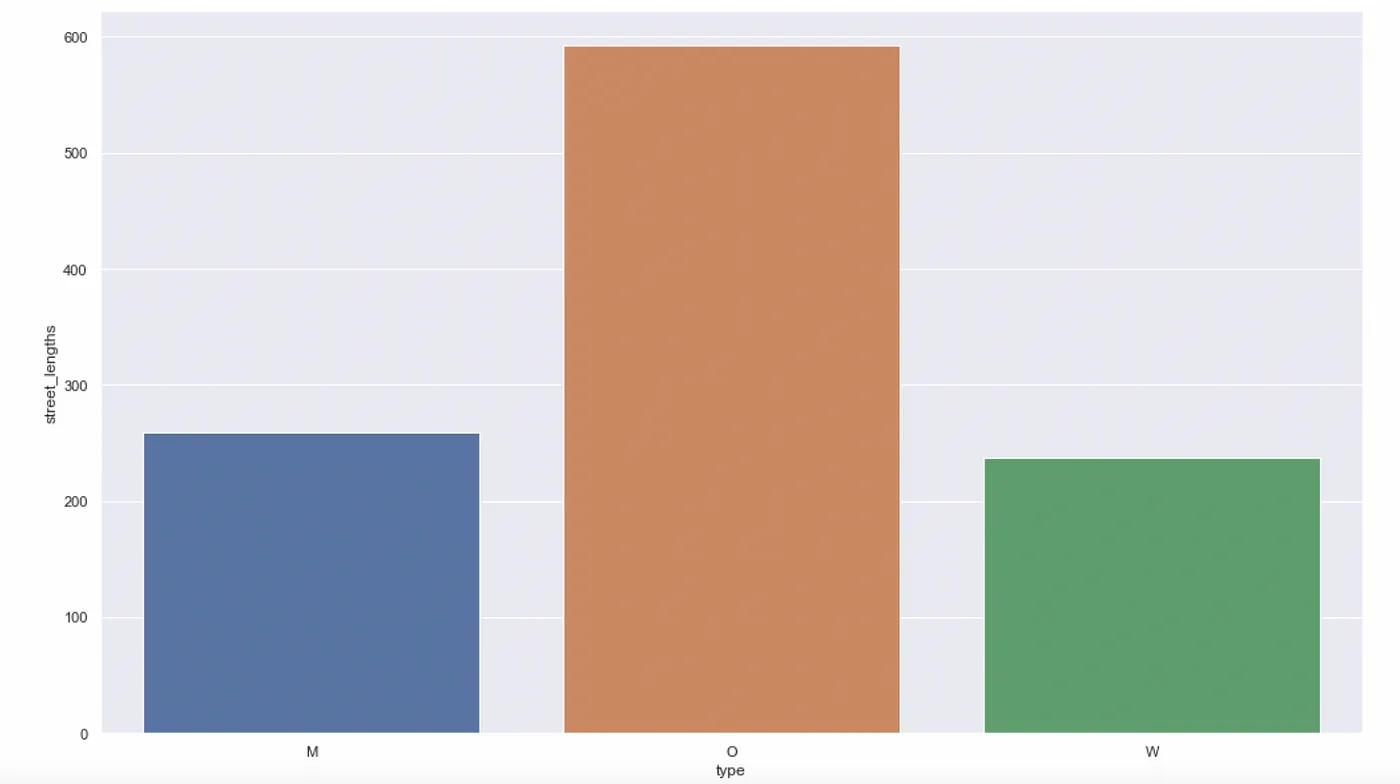

Let’s take a look at the total lengths of all streets grouped by gender. To do this, I projected the linestring geometries to a projected coordinate system that used meters and averaged their length by gender:

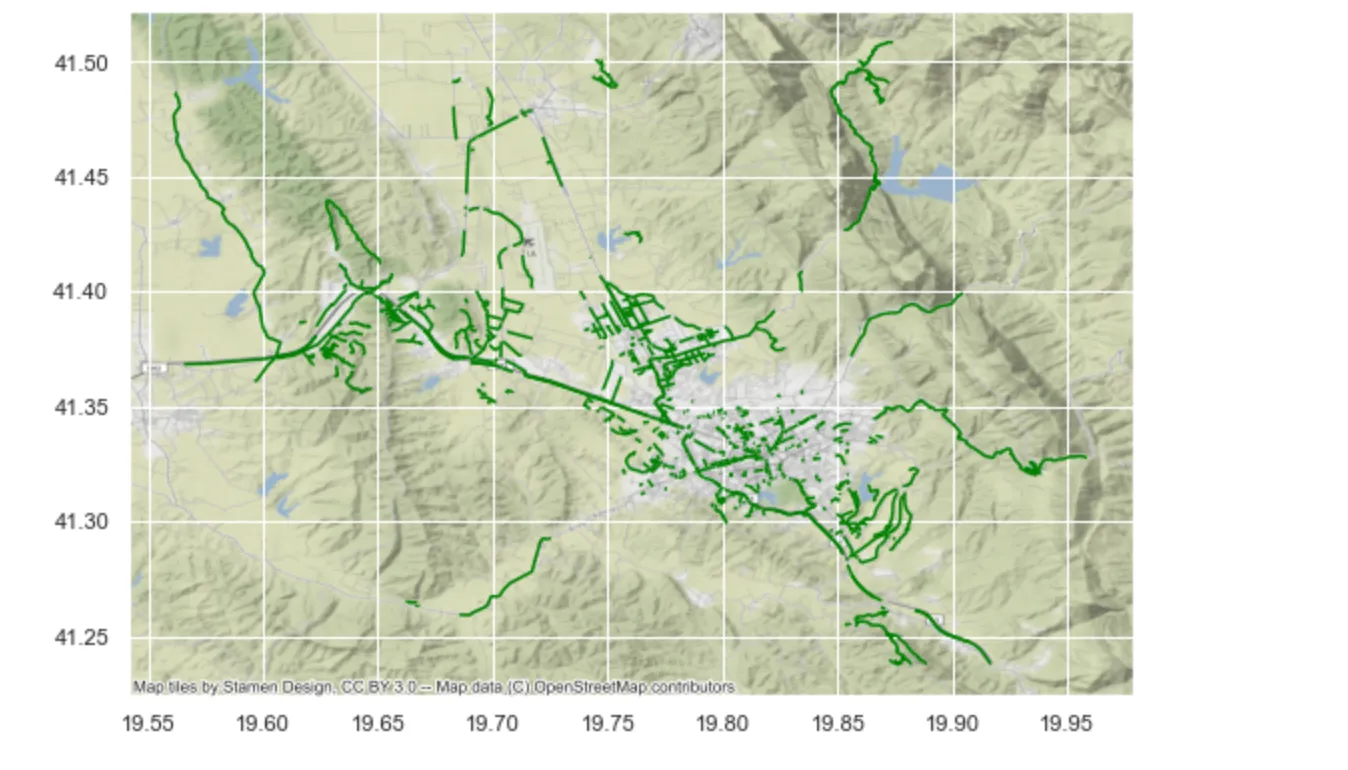

Interestingly, “Other” streets are the longest on average, and streets named after women are slightly shorter than those named after men. It also appears that “Other” streets are found in highways or peripheral streets that are away from the urban core of Tirana:

This can be explained by the fact that highways or other inter-city streets had names such as “Tirane-Durres” signifying the two urban centers they were connecting or simply highway codes such as “SH1”. Given that, I labelled these streets as “Other”.

And here are the maps for streets named after men vs. women:

Map of streets named after men (Image by Author)

Map of streets named after women (Image by Author)

Professions and Work

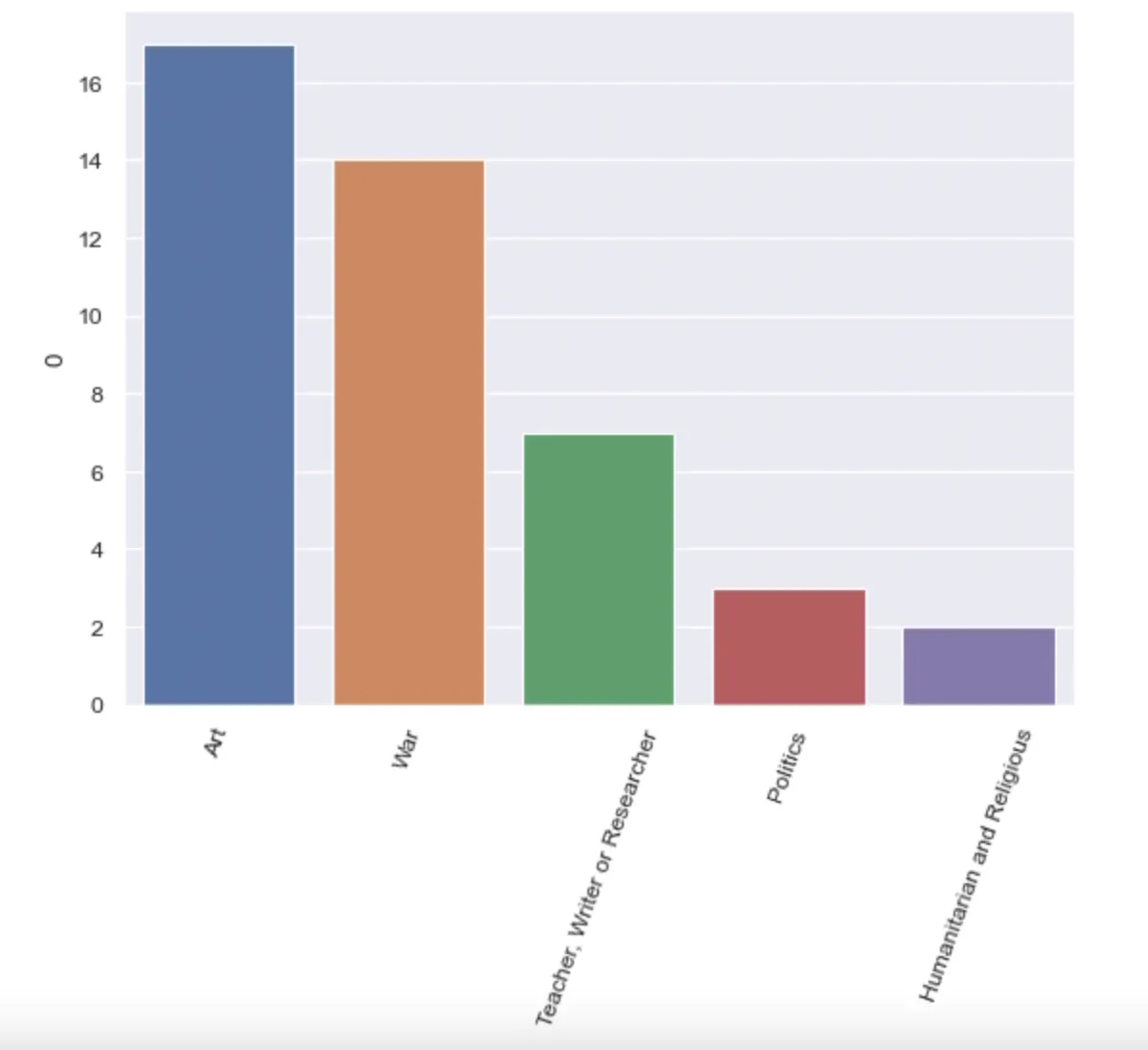

In what area has each of these women’s contribution been? I divided the professions in a couple of categories and here are the results (some of the figures had no available information online):

My categories were (broadly):

- Art, Teacher/Writer/Researcher, Politics, Humanitarian and Religious and War (for some context, many of these women fought alongside men in WWII and they represent the majority of women belonging to the “War” category):

Neighborhoods

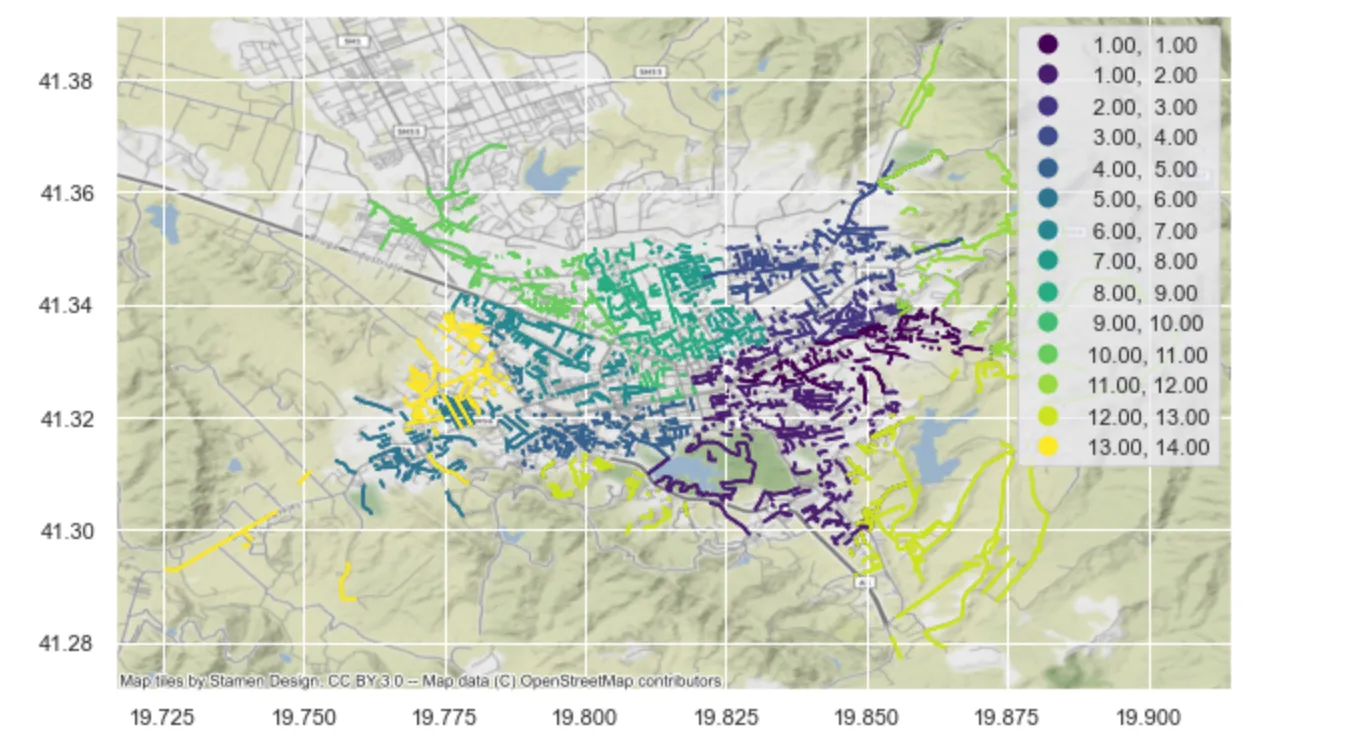

In addition to fields of contribution, are there any patterns in how the street names are divided by neighborhood? Tirana has 14 administrative areas dividing the city into distinct zones. Using a GeoJSON file from OpenStreetMaps that shows the polygons of each of these areas, we can perform a spatial join of this dataset with that of the street names. Here is a map of the 14 areas:

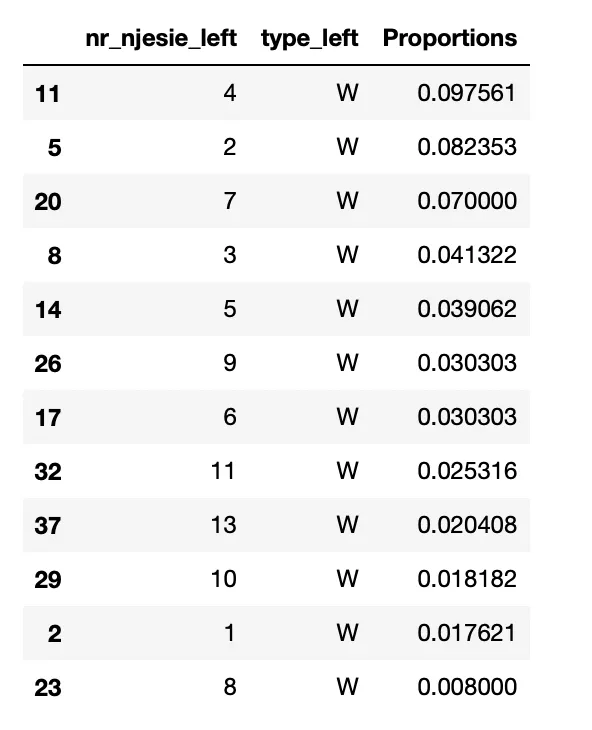

I’m interested to see what proportion of the street names in each administrative area are women:

There are some interesting findings (at least to me :) ) . There are quite a few discrepancies in the proportions of women’s names, with areas like no. 4 having almost 10% of streets named after women and no. 8 having 0.08%. On the other hand, two of the areas (12, 14) had no streets named after women. Again, it would be interesting to look into the decision-making processes behind these naming choices.

Occupations and Historical Periods

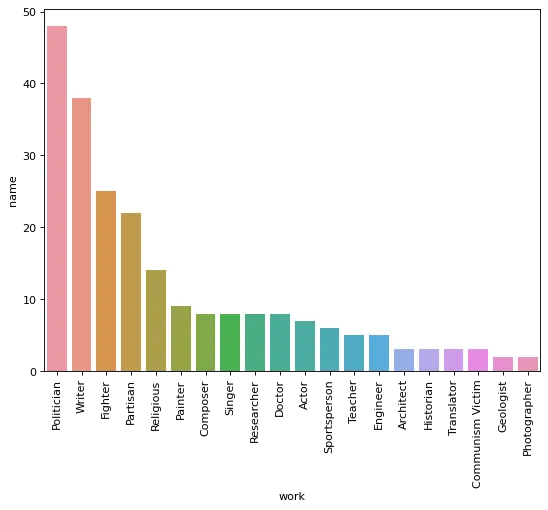

When labelling the data, I classified each person into a few broad categories depending on their Wikipedia page. It turns out there are 62 unique occupations among the street names! Here is a bar plot of the top 20 and their respective counts:

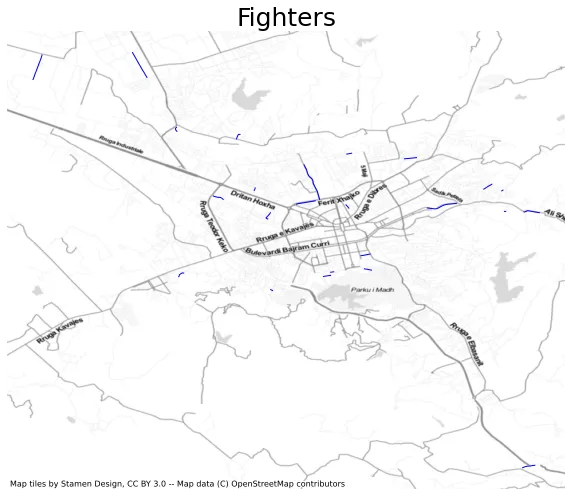

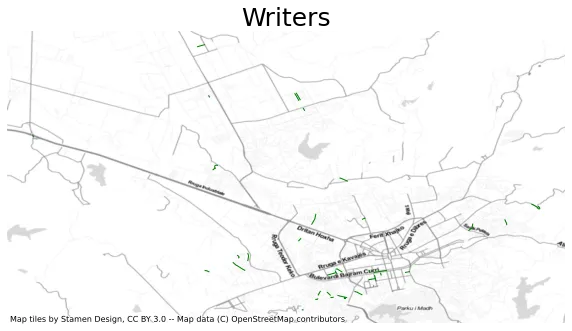

Note the prominence of politicians, fighters and writers: these 3 categories together make up approximately 40 percent of all labelled street names in the data. Artists follow suit, rounding out the rest of the top 10. I made the choice to label partisan figures (8% of labelled total) separately from the rest of fighters, because of their direct associations with the period of the Communist regime in Albania (1946–1991) and the propaganda they were made a part of during this time. Therefore, I believe this deserves its own consideration as part of a broader conversation on how we reckon with our history as a country.

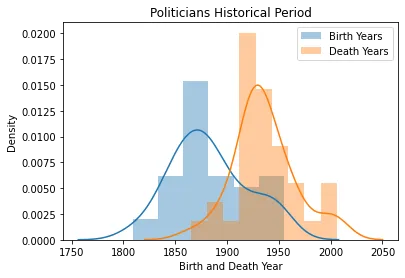

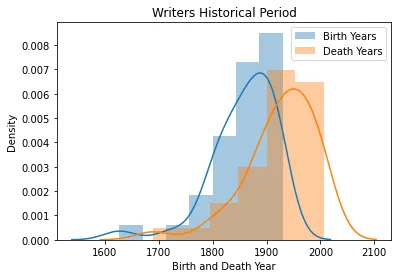

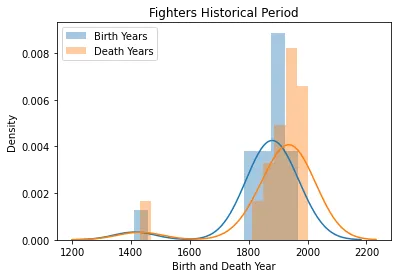

Let’s take a better look into the top 3 categories: politicians, writers and fighters. Specifically, what are the historical periods they lived and worked in? Here is a distribution of the birth and death years, as well as the mean values for both of them:

- Mean birth year: Politicians (1882), Writers (1858), Fighters (1853)

- Mean death year: Politicians (1936), Writers (1925), Fighters (1900)

There are some interesting patterns to be noticed in the graphs and the average statistics above: firstly, it seems the majority of these figures were active in the period between the 1850s to 1930s. This seems to be less of the case for writers, which are represented in the 17th and 18th centuries as well. There is also a peak in the “Fighter” birth and death years, corresponding to the Skanderbeg-led period of rebellion during the Ottoman Empire invasion. Skanderbeg (1405–1468) is recognized as our National Hero and is widely honored in many monuments, squares and institutions to this day. The 19th-20th century, on the other hand, corresponds to the period of the Albanian National Awakening which was a cultural and political movement seeking to establish an independent country of Albania.

Streets named after women

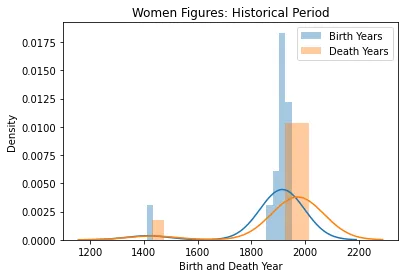

Last time, we looked at how women-named streets made up approximately 3% of the total names, but let’s take a look at these streets in their historical context and occupation as well. Filtering by gender and taking a look at the same birth/death distributions:

- Median birth year: 1912

- Median death year: 1949

Here, there are some interesting patterns too: first, I chose to take the median instead of the mean because it would have been greatly influenced by the small spike around the 1400s. This results in a shift in time of the era of women’s activity, compared to the overall distributions. In part 1, we saw that many of these women were in the arts or had fought in various wars, which can explain the median death year.

Mapping it out, Neighborhoods and Road Types

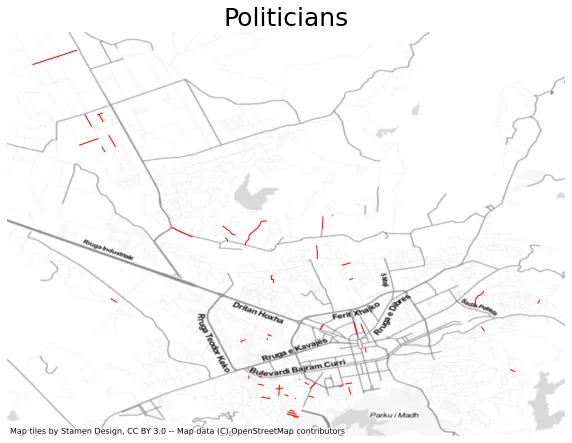

Let’s take a look at how all of this looks from a geography perspective. Here are three maps for each of the top 3 categories:

I would say I can’t pick out any immediate patterns just by looking at the data. To start to see if there are any, here is also a look into the most common occupations in each of Tirana’s 14 administrative areas (the polygon data for the administrative areas which is merged with the street names also comes from OpenStreetMaps):

Not surprisingly, politicians and writers still feature prominently: what I think might merit more thinking is how certain areas have religious or partisan figures as their most common occupations. This might point at particular figures originating from those neighborhoods as a form of local representation, or other interesting patterns to look into.

Names with no information on the internet

As I mentioned in the beginning, a large part of these streets’ names had no readily available information about them online. According to the labelled data, they comprised about 55% of the streets named after people. I found this to be an interesting phenomenon as it could mean many things such as these names being locally important figures but perhaps not widely recognized, or the (obvious) fact that the internet has a limited amount of information and one would need to look into other sources. Here is a visualization of where all of these names were located (note how these names feature in the periphery, rather than in the more urban core of the city):

Final Thoughts + the Code

Overall, this story looked at Tirana’s streets landscape from a more historical lens. We delved deeper into how different work areas and historical periods were represented and uncovered patterns across both these aspects. In addition, there’s a few other directions to take this project: some questions that come to mind are how the names have changed over the years as the city has grown and changed, or even what specifics to the naming process lead to the distributions we saw. For now, here is the Jupyter Notebook and the dataset for this post. Hope you enjoyed!

If you like these urban planning-themed posts, you might like my newsletter in which I talk about these topics even further: The Zoned Out Chronicles!